*A few spoilers below, but not too bad

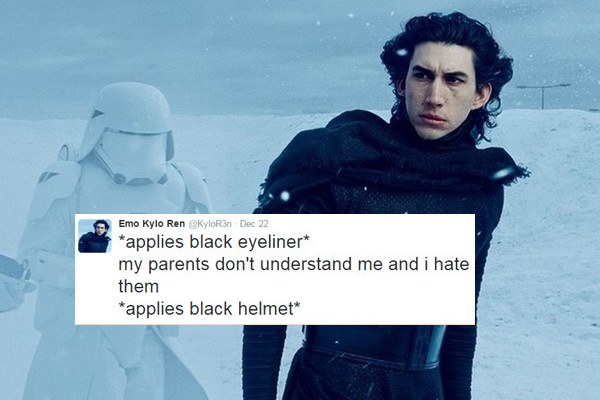

In The Force Awakens, J.J. Abrams brings a volatile new villain to the screen: Kylo Ren, the latest apprentice of the Dark Side, plagued by fits of rage and the same family hang-ups faced by many characters in the Star Wars franchise. But unlike most other Star Wars villains, Kylo has been called “ultra-privileged,” and “a school shooter” “sulking through his early life.”

Speaking just as a Star Wars fan, I thought these accusations were completely out-of-place. They made about as much sense as calling Macbeth “ultra-privileged”: the insult doesn’t quite work somehow. Sure, Kylo Ren has serious flaws: he kills and tortures people, and takes out his anger on inanimate objects. But “ultra-privileged?” Try “power crazed” or “despotic.”

I can’t help but feel that if Kylo Ren had kept his mask on the entire time, and never revealed the face of a young man, “ultra-privileged” would never have crossed anyone’s mind. Keep everything else about his character the same—the same nefarious mission, the same arrogant speech, the same casual sadism—but never show his face. Suddenly, he’s become his grandfather, Darth Vader: “more machine now than man, twisted and evil.” It’s only when his young face is revealed that we think to call him “a petulant little brat” rather than just a machine off its rails, like Vader.

But whichever adjectives we use, there’s no denying Kylo Ren is an unpleasant character. And the unfortunate fact is that there’s nothing at all to stop a crazed, unstable, patricidal villain from also happening to be a young man—just as there would be nothing stopping him from being black, or gay, or Jewish, or left-handed. But why is he a young man? Does he have to be? Of course not. This is why, for the millionth time in history, we’ve arrived back at the Merchant of Venice debate: when is it okay to write a villain who’s also a member of some scapegoated social group? Do we always have to write in enough villain characters to make sure that every demographic is proportionately represented among the forces of evil?

As a writer, I find these kinds of rules silly and oppressive. Real life doesn’t work that way. Personally, I’d like to place more of the burden on the viewers than the artist. I’ve had the experience of creating fictional young characters I thought were complex and well-developed. But some of my readers dismissed them as “selfish snots who should be in a mental hospital.” For this reason, I’m inclined to give J.J. Abrams more credit—or at least not to give him credit for people’s negative reactions to Kylo Ren.

However, my authorial bias aside, I’ve noticed a progression in the Star Wars franchise that might require me to retract my own generosity. Star Wars—like the modern youth rights movement—began in the aftermath of the 1960s, during which the old ways had just been challenged by youth movements. Accordingly, in the original trilogy, the heroes are rebels: the young and virtuous (Luke and Leia) fighting the corrupt and tyrannical (Darth Vader and the Emperor). In this story, it’s the young who redeem the old. “You were right,” the dying Darth Vader tells his son, “You were right about me.”

Now, let’s fast forward to 1999, the start of the prequel trilogy, and the beginning of the Columbine era. In Attack of the Clones (written in 2000), we’re introduced to an adolescent Anakin who rebels against his elders, and ends up turning to the Dark Side and murdering droves of innocent people. What did the council of wise Jedi elders do wrong? Against their better judgment, they gave this young man too much responsibility. If they’d kept him marginalized—as any “responsible” adult should have—the Old Republic may never have fallen, and the wise senior Jedi would still be in charge.

Kylo Ren may just be evidence that little has changed since 2005, when the last of the three prequels was released. Sure, corruption of Jedi apprentices is a running theme in the Star Wars universe. But the problem is that corruption also happens to older people, as Charles Dickens spent his whole career proving. And then there’s Citizen Kane and Breaking Bad, and a thousand other wonderful examples of stories where older adults are seduced by their own versions of the Dark Side. Why couldn’t Anakin or Kylo Ren have fallen from grace as middle-aged adults?

But we’re forgetting that this is Disney. They profit largely off the familiar, and so they always leave room for popular sympathies, and popular bigotries. The last thing on their list of priorities is to challenge these. To make the new Star Wars completely proof against ageist bigots would require Disney to do what Disney by definition can’t do: force viewers to confront a controversial truth.

Of course, we should expect filmmakers as a whole to challenge people’s opinions, and we’re right to be frustrated when they don’t. But J.J. Abrams directing a new Star Wars movie for Disney is simply the wrong vehicle for this kind of challenge. I’d say the best we can do for youth rights in response to The Force Awakens is to claim it as neutral territory that doesn’t necessarily support ageism. As of this first movie, I believe that this is still a viable position—especially since there are other young characters who aren’t unstable psychopaths. In any case, The Force Awakens is certainly superior—both from a youth rights perspective, and a Star Wars perspective—to the 1999 prequel trilogy. In the meantime, we should continue to demand more from Hollywood in general, and especially from viewers—without whom Hollywood would never change in any case.