The rights of young people are increasingly threatened as schools implement more policies designed to police and punish a wide range of behaviors. Many of these policies are known collectively as part of the “school-to-prison pipeline.” They involve a variety of elements including increased police presence, unreasonable rules, a failure to respect students’ right to due process, and harsh punishments. Through these policies, schools ultimately treat students like prisoners and therefore undermine their rights in the education system.

Unreasonable rules

At school, young people must tolerate rules that many adults would consider unacceptable in the workplace. These can include rules prohibiting high-fives, talking during lunch, only allowing scheduled bathroom breaks, and giving students less lunch time than is required by federal employment guidelines. In fact, schools have some of the strictest rules of any government institutions, harsher than those at national parks and public libraries.

Zero tolerance

Zero tolerance policies are policies that severely punish any violation of a rule, regardless of the particular circumstances of each case. For example, a zero tolerance policy might require a school to expel any student who gets into a fight, even if that student was fighting in self-defense or to defend a friend. Zero tolerance has led to students being suspended or expelled for holding up three fingers in a school photo, having a clear plastic toy gun in a backpack, or even disarming a school shooter and saving other people’s lives.

These policies are unfair and don’t make schools safer. By treating all cases the same schools ensure that real problems remained unaddressed. In one study, a task force reviewed 10 years of research on the effects of zero tolerance policies in middle schools and secondary schools. The task force concluded that zero tolerance policies not only fail to make schools safer or more effective in handling student behavior, but they actually increase instances of troubled behavior and dropout rates. Students that are punished for minor infractions can feel unwelcome in their own schools and violates their right to due process.

School disruption charges

At least 22 states and many cities and towns make school disruption a crime. While these laws were initially enacted to prevent outsiders from disrupting a student’s right to education, they are often broad and confusing to understand. The vagueness of the laws means they are inevitably applied unevenly, depending on the moods and biases of the adults enforcing them. For example, South Dakota definition of disruption includes “boisterous” behavior, while Arkansas outlaws “annoying conduct.” These unclear rules leave students vulnerable to unfair treatment, because they can potentially be punished for any behavior that adults decide falls under these categories.

These laws are oftentimes overused as well. In South Carolina, disturbing school was the second-most common accusation used against juveniles after misdemeanor assault – which amounted to an average of seven students were charged every day.

Additionally, judges across the country have different definitions of “disturbance,”which can complicate the issue of school disruption charges even further. In Georgia, a court concluded that a fight qualifies as disturbing school if it attracts student spectators. However, a Maryland court found that attracting an audience does not create a disturbance unless normal school activities are delayed or cancelled. In Alabama, a court found that a student had disturbed school because his principal had to meet with him to discuss his behavior. An appeals court overturned the ruling on the grounds that talking with students was part of the principal’s job. Clearly, there is no consensus on what disruption means or when students should be punished for it. This leaves young people at risk during the school day, when they should be able to learn without fear of being punished for something they don’t even realize is “illegal.”

Increased Police Presence

Increased police presence in schools and the use of school resource officers (SROs) have turned many schools into police states. They escalate everyday discipline issues into law enforcement issues and turn ordinary rule-breakers into criminals.

Juvenile Justice agencies focus on probation and develop school based programs to increase overall effectiveness with youths under supervision of the juvenile court.

Studies have shown that school programs specially designed to get services for at-risk youth can reduce the rate of serious juvenile delinquency while also improving performance. However, experts believe these programs must be adopted with caution. This is because research shows that officials are more likely to involve minority youths in the justice process than white youths, even when their misbehavior is the same.

Courts may get involved with potential delinquent juveniles through promoting effective programs to address the needs of youth who might be at risk of entering the juvenile justice system. Current research has proven that effective programs include those that aim to act as early as possible and focus on known risk factors.

Some programs shown to be effective include:

- Classroom and behavior management programs

- Multi-component classroom- based programs

- Conflict resolution and violence prevention curriculums

- Bullying prevention programs

- After school recreation programs, sports

- Mentoring programs

- School government associations

In the mid 1970s, only about one percent of schools had sworn police officers. In the 2013-2014 school year, that number had risen to twenty-nine percent. Schools with higher percentages of minority students generally had more school resource officers, other sworn officers, and security personnel, while they were less likely to allow students to carry backpacks and cellphones. This criminalizes students before they even have a chance to enter the building, creating a hostile environment and lack of trust.

Calling the police for breaking school rules

Many public schools criminalize nonviolent school misbehavior such as class disruption and profanity. This means that instead of speaking to a teacher or counselor and addressing the root of the problem, the student is given a punishment that does not fit the crime. Sometimes students must pay a fine—something that many families cannot afford. Sometimes students may even go to jail, increasing their likelihood of remaining inside the criminal justice system. Whenever misbehavior goes on the student’s permanent record, it damages their ability to find housing or a job later in life.

Many people defend this level of strictness by pointing out the need for order and safety in schools. They say that students need to learn that their actions have consequences, and having tough, clear rules is the best way to teach this.

However, this lesson works both ways. People in charge of school discipline also need to learn that their actions have consequences. When they arrest students, they are depriving another person not only of liberty, but also education, community, and the chance of a proper future. The main purpose of school discipline should be to keep students out of prison—not to funnel them into it. When educators fail at their job and send students to court, they create a school-to-prison pipeline, which is one of the worst signs of the public school system’s failure. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, students that are arrested are three times more likely to drop out, even if their case never goes to trial. There are also more likely to reenter the criminal justice system as adults. This criminal record follows them into adulthood.

School resource officers

School resource officers (SROs) are sworn law enforcement officers who also have disciplinary authority in schools. Their main jobs are to enforce, counsel, and educate students about the law. SRO programs say that their goal is to keep students safe and to develop a positive relationship between students and law enforcement.

In practice, SROs often do the opposite of what they are supposed to do. SROs play a key role in criminalizing student behavior. They are usually the ones who arrest students on misdemeanor and/or felony charges for incidents that should be handled by the school administration. This escalates minor everyday conflicts into crimes. For example, because of SRO involvement, shooting spitballs becomes misdemeanor assault, and a misunderstanding about a carton of chocolate milk becomes petty larceny.

SROs are disproportionately present and make more arrests in poorer and high-minority schools. Students attending schools with SROs are also five times more likely to face criminal charges for disorderly conduct at school: something that was not a crime before.

With police presence, schools also must suffer from problems with policing in general. For example, the use of excessive force is now not only a problem for people on the street—it’s also a problem for students in school. One student was slammed to the ground by an SRO when she tried to rescue her sister from a fight. A Muslim student was arrested for bringing a homemade clock to school. At a school in Georgia, police conducted invasive body searches of all 900 students without reasonable suspicion.

School resource officers are also expensive to maintain. In addition to paying SROs each an average of $60,000 a year, each student they arrest can cost thousands of dollars to the state, and to families. The expenses are even higher when young people get locked up. Juvenile detention facilities spend yearly an average of $88,000 per inmate, with some states going as high as $150,000 per inmate. School resource officers are not only expensive, but have a high social cost as well.

Punishments

Increased policing in schools also happens when students are subjected to unreasonable punishments and are denied basic rights when when subjected to these punishments.

These policies and procedures frequently deny students the protections of due process, including the right to understand the charges, avoid self-incrimination, and appeal punishments.

Public school students do not have the same right to due process that school employees or people outside of school have.

General due process rights include:

- Understand the charges/Know what specific rules were violated

- Hear a description of the evidence against

- Have punishments decided by an impartial third-party

- Have a chance to tell their side of the story

- Bring evidence and witnesses on the student’s behalf

- Bring legal counsel

- Specific information about the charges and the evidence behind it.

- A chance to tell his or her side of the story.

- the due process requirement can be met with an informal conversation in the principal’s office.

- Have the right against self-incrimination

- Cannot have evidence submitted against them that was obtained illegally.

This means that:

- Students do not have the Fifth Amendment right to remain silent to avoid self-incrimination. Students can be punished simply for not answering the questions of school officials. Many schools employ Student Resource Officers (SROs), who have less of an obligation to read students their Miranda warning in school than they would outside of school.

- Students don’t have the right to a lawyer when questioned by school officials. In many states, students do not even have the right to have a lawyer present at hearings for severe punishments like suspension and expulsion.

- Students can be detained without a hearing, based only on reasonable suspicion or as a punishment, such as in-school suspension.

- School officials have much greater power to search students, often needing much weaker standards than are required when police conduct searches of school employees or people outside of school.

School officials claim that students are denied the same due process standard as adults because of the need for order and discipline in schools. In fact, many people believe that constitutional protections are actually harmful for students, since they undermine the ability for teachers to maintain order in the classroom. In Goss vs. Lopez, Supreme Court Justice Powell said that constitutional protections for students would be “a challenge to the teacher’s authority…”

Our society believes that it is bad for young people to challenge adult authority, and having constitutional protections would enable this kind of behavior. However, Constitutional protections exist because without them, we cannot be truly safe from abuse by government officials. There is no reason why public schools should be a unique environment in which constitutional protections are weakened, and sometimes do not apply at all. Students deserve the same due process that would be granted to any adult when a government official tries to punish them or deny them government services.

Cruel and unusual school punishments

In addition to suspension and expulsion, schools use a wide variety of bizarre punishments, including being publicly forced to hold hands, spend hours in an isolation room, or sit half naked in a chair. Although the teachers and administrators responsible for these punishments are sometimes suspended or fired, this is rare because firing teachers is very difficult. In any case, disciplining a teacher or administrator for using cruel and unusual punishment on students cannot undo any damage these punishments might have caused.

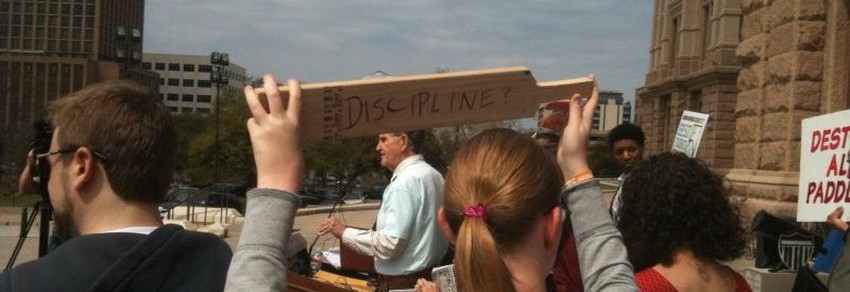

Government officials are also allowed use corporal punishment on students, as long as these officials work for the school. Everywhere except in school—the workplace, the military, and even prisons—corporal punishment by government officials is unconstitutional: a form of cruel and unusual punishment that is against the Eighth Amendment.

Suspension and expulsion

Among disciplinary practices that often ignore students’ constitutional rights are suspension and expulsion – two forms of exclusionary discipline that simply take a rule-breaker out of the school environment. This practice ignores critical teaching moments in which students can learn from their possible mistakes and instead plays on the fear that rule-breakers may negatively influence teachers or other students.

The Supreme Court case Goss v. Lopez decided that students have the right to a hearing before being suspended. They also have the right to a hearing before being expelled. Education is a “property and liberty” interest that is protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, which says that the government cannot take it away from students without due process. Students must be permitted a hearing and allowed to speak before being suspended or expelled.

This type of disciplinary action can cause a student to forfeit the right to free and universal education. Although in some states, such as Pennsylvania, the government must guarantee expelled students an education elsewhere, not all states have this requirement. In Massachusetts and Wisconsin, for example, many students are denied the right to attend any public school (“expelled to nowhere”).

Using suspension and expulsion on a regular basis does not make schools safer or better in any way. It also causes serious harm to the punished students academically, socially, and psychologically.

Recently, schools have faced pressure to reduce suspensions and expulsions. Some schools break the law by not documenting suspensions, but instead pass them off as unexcused absences or medical leave, or simply leave them “off the books.” Marking students as an “unexcused absence” can lead to the student being charged with truancy. Schools that send students home without a formal suspension are breaking the law.