According to the American Medical Association, the right to informed consent to medical treatment is considered to be fundamental both ethically and by law. However, young people are usually denied this right, and are forced into treatment without consent, or prevented from obtaining necessary treatment, even when recommended by a medical professional. The right to make informed medical decisions is one of the most basic human rights and should not be denied to young people.

Access to medical information and confidentiality

A key component of medical consent is the right to access medical information, and keep medical records private. This is another basic right that is denied to young people.

The average patient can control their own medical records and decide who gets access to them. Young people on the other hand do not have this right to medical confidentiality. This has unseen health consequences because people are more likely to seek medical care if they believe their provider will keep their information private.

Young people can be also denied access to basic information regarding diagnosis and treatment, simply at the request of their parents. The Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) of 1990, which required health care providers to inform patients of all relevant information about their condition and prognosis, educate them about their options, and leave the choice up to the patient’s best judgement prior to any action. It does not apply to youth because the mere state of being under 18 automatically deems that patient incompetent to provide legal consent. Their largest downfall, by far, is a simple lack of knowledge, which could cause a patient of any age to appear intellectually incapable. Everyone, regardless of age has lapses in judgment and can make poor decisions, but nobody can make a wise decision when they are deprived of all pertinent information on the matter. A vicious cycle exists in the refusal to educate kids on their medical conditions. The only reason young people are denied the right to make their own medical decisions is because they are also denied the right to receive medical information. Although medical rights were expanding for adults, progress for minors continued to be hindered by the faultless factor of age.

Other obstacles to receiving medical care

Sometimes parents prevent young people from receiving medical care because it goes against their religion or personal beliefs. When the values of young people explicitly conflict with the values of their parents, those values can be disregarded entirely. While in many states, parents can be prosecuted for denying their children medical care, 34 states have laws exempting caretakers from criminal liability if the parent makes medical decisions for their child based on religious beliefs, including six states that provide a religious exemption against manslaughter.

The right to refuse treatment

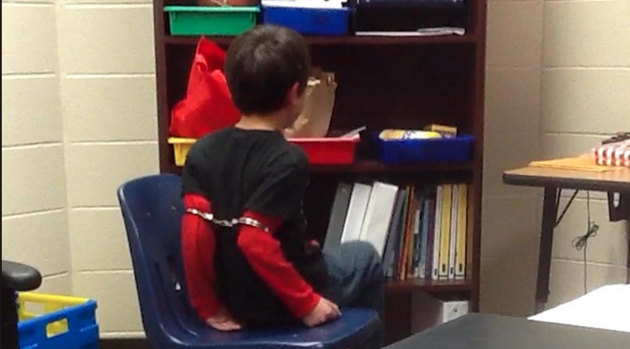

Sometimes, young people who wish to refuse medical treatment have the support of their parents. In these cases, young people can be forced to undergo treatment anyway by the state and their parents are not allowed to act on their behalf. Young people may also be removed from their homes in order to coerce them into receiving treatment. In fact, courts have forced people who are months away from their 18th birthdays in this manner even when they can clearly articulate their reasons for refusing the treatment.

Cassandra C.

In the case of Cassandra C., it was concluded for the state of Connecticut that she was not a mature minor. Their reasoning was that people under 18 must be assumed incompetent to give consent, so it is the responsibility of the individual to provide evidence that proves their competence, which they did not believe Cassandra did.

An excerpt on page 16 of the case states the following:

“Under the authority previously set forth, there is a legal presumption that Cassandra was not competent to make the life or death decision whether to undergo chemotherapy treatment for her cancer because she was not yet 18, and the burden was therefore on the respondents to establish that she was sufficiently mature to do so. Because the respondents failed to produce any evidence on that factual issue, despite being on notice that that was the purpose of the hearing, there was no basis for Judge Quinn to find that Cassandra was a mature minor under any standard.”

The mature minor doctrine

There is a way for some young people to have medical autonomy through what is known as the mature minor doctrine. This policy states that if someone under the age of majority is able to demonstrate a sufficient level of maturity and understanding of their condition, they will be granted the liberty to refuse or consent to treatment without permission from their parents.

The idea of a mature minor doctrine spawned from the court case of Smith v. Seibly (Washington Supreme Court, 1967), when the court determined that physicians may consider factors such as “age, intelligence, maturity, training, experience, economic independence or lack thereof, general conduct as an adult and freedom from the control of parents” when determining whether unemancipated individuals may consent to surgery. The court also referred to a previous case, Grannum v. Berard (Washington Supreme Court, 1967), which said, “The mental capacity necessary to consent to a surgical operation is a question of fact to be determined from the circumstances of each individual case.” A precedent was hence set for differentiating between different people of the same age.

The People of The State of Illinois v. E.G. (1989):

A Jehovah’s Witness just shy of her 18th birthday was in need of blood transfusion due to her leukemia. Both she and her mother refused the treatment and this decision was upheld because she was determined to be competent enough to consent. Two judges dissented on the grounds of parens patriae, a principle stating that it is the government’s obligation to keep its defenseless citizens out of any avoidable harm. The court ultimately concluded that they did not wish to set a precedent for the standards of the mature minor doctrine.

Dane County v. Sheila W. (2013):

15 year old Sheila had a similar scenario to E.G.; she had aplastic anemia and required blood transfusions, but as a Jehovah’s Witness, she refused with the support of her family. The county concluded that Shelia’s parents were endangering her, and took custody of her, placing her under the authority of a temporary guardian, who consented to the blood transfusion. Sheila did appeal to the treatment, but her case was dismissed on the grounds that the dispute had already been solved, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court declined to review the social policy around the mature minor doctrine.

Belcher v. Charleston Area Medical Center (1992):

17 year old Larry was hospitalized and placed on a respirator after a choking incident. After a discussion between his parents and physician, Dr. Ayoubi, it was decided that he would not be resuscitated. Larry was able to communicate at this time, but was never consulted. The next day he suffered another respiratory attack and died. Because Dr. Ayoubi never received Larry’s consent for the “Do Not Resuscitate” order, the medical center was sued for medical malpractice. The Charleston Area Medical Center, however, was found not be liable because Larry was a minor. The West Virginia Supreme Court ruled that “except in very extreme cases, a physician has no legal right to perform a procedure upon, or administer or withhold treatment from a patient without the patient’s consent, nor upon a child without the consent of the child’s parents or guardian, unless the child is a mature minor, in which case the child’s consent would be required.”

The vast majority of United States jurisdictions still do not recognize the mature minor doctrine by law and parental consent remains mandatory. All states have varying provisions that may allow someone to consent to medical treatment even if below the age of majority, the most common being pregnancies, separate living situations, emancipation, marriage, and enlistment. However, these circumstances are often unachievable for young people and none of them necessarily signify competence anyway. At least 37 states have statutes permitting citizens under 18 with children to make medical decisions for themselves, their children, or both, and yet no states have created an actual, applicable mental evaluation for the matter. This is an illogical and unjust method of determining competence. When young people are denied the right to medical confidentiality, they are really just deprived of medical information about their condition.

The law on medical consent

Chart summary of mature minor doctrine by state:

| State | Mature minor doctrine | Emergency care | General Medical | Reproductive | Confidentiality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Yes | y | y | partial | n |

| Alaska | Yes | y | y | y | unknown |

| Arizona | No | y | n | y | y |

| Arkansas | Yes | y | y | y | y |

| California | No | y | n | y | n |

| Colorado | No | y | n | y | y |

| Connecticut | No | y | y | y | y |

| Delaware | Yes | y | n | y | n |

| District of Columbia | No | y | n | y | y |

| Florida | No | y | n | y | n |

| Georgia | No | y | n | n | n |

| Hawaii | No | y | n | y | n |

| Idaho | Yes | y | Only for certain diseases | y (excludes abortion) | Only for drug abuse rehab |

| Illinois | Yes | y | n | y | Provider is not obligated, but allowed to inform parents |

| Indiana | No | y | n | y | y |

| Iowa | No | y | n | y | n |

| Kansas | Yes | y | y | y | y |

| Kentucky | No | y | n | y | y |

| Louisiana | Yes | y | y | y | y |

| Maine | In exceptional circumstances | y | n | y | n |

| Maryland | No | y | n | y | n |

| Massachusetts | Yes | y | n | n | n |

| Michigan | No | y | n | n | n |

| Minnesota | No | y | n | y | y |

| Mississippi | No | n | n | y | y |

| Missouri | No | y | n | y | y |

| Montana | For high school graduates | y | n | y | n |

| Nebraska | No | y | n | y | n |

| Nevada | In exceptional circumstances | y | n | y | n |

| New Hampshire | No | y | y | y | n |

| New Jersey | No | y | n | y | y |

| New Mexico | No | y | y | y | n |

| New York | No | y | n | y | y |

| North Carolina | No | y | n | n | n |

| North Dakota | No | y | y | y | y |

| Ohio | No | y | Situational | y | y |

| Oklahoma | No | y | n | y | y |

| Oregon | Yes; excludes refusal | y | y, if over 15 | y | n |

| Pennsylvania | For high school graduates | y | n | y | y |

| Rhode Island | No | y | Y, if 16 | y | y |

| South Carolina | Yes | y | Y, if over 16 | y | n |

| South Dakota | No | y | n | y | y |

| Tennessee | Yes | y | n | y | y |

| Texas | No | y | n | y | n |

| Utah | No | y | n | y | n |

| Vermont | No | y | n | y | y |

| Virginia | No | y | Y, if over 15 | y | y |

| Washington | No | y | y | y | n |

| West Virginia | Yes | y | n | y | n |

| Wisconsin | No | y | n | y | n |

| Wyoming | No | y | n | y | n |

Guidelines used by medical professionals

According to the American Medical Association, it is encouraged that physicians allow “competent minors” to consent and that the parental guardians are not involved without the patient’s permission. They also state that “incompetent minors” should still receive certain types of care if the patient would be in danger otherwise. These types of care include contraception and treatment for pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases, drug abuse and mental health issues. When evaluating whether or not a patient is competent, physicians are to seek the criteria of experience, autonomy, intellect, perceptivity, and of course, maturity.

A legitimate comprehension exam is not about giving children unbridled freedom, it is about supplying them with their birthright of proving their mental capacity and earning their rights to govern their own bodies. Practices like the mature minor doctrine are vital in upholding the protection and justice of those with the least power, but they must start providing an alternative to marriage, pregnancy, or enlistment. When adolescents do not have proper representation, their only means of defense is the law, and so it should never be lawful to deprive young people of the resources they need to defend their rights.

Affirming the Decisions Adolescents Make about Life and Death

Improving the Mature Minor Doctrine/Fraser guidelines and Gillick competency

The standards England uses to determine the competency of young people to consent to or refuse medical treatment are superior to the ones used in the United States. Their two standards are the Fraser Guidelines and the Gillick competency test.

In 1986, the English case of Gillick v. West Norfolk went to court. Victoria Gillick contended that under the law, doctors should not be able to prescribe contraceptives to adolescents under the age of 16 without parental consent.

When her complaint was declined, two major legal developments emerged from the court’s ruling. One of these advances was the Fraser Guidelines, which underlines the stipulations that doctors must satisfy before they can provide contraceptives to minors under 16 years old. Lord Fraser pointed out that minors can enter into contracts, sue, be sued, and testify under oath, so the law has already deemed them mentally qualified in some circumstances.

The Gillick competency is better than the Mature Minor doctrine because it applies to everyone over 16 and is used federally. Yes, minors are usually assumed Gillick Competent at age 16. In the U.S., that age varies by state and by kind of treatment….. In some states it would be easier, and in others it would be much harder, depending if you seek an abortion, mental health services, STI testing, etc. And those change under the circumstances of having moved out, getting married, having a baby, so on so forth.

The other product of this case was Gillick competency, which states the standard that “Parental right yields to the child’s right to make his own decisions when he reaches a sufficient understanding and intelligence to be capable of making his own mind on the matter requiring decision.” This criterion has been successfully employed in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland it seems to be a fair and functional remedy. To determine if a child is “Gillick competent,” their pediatrician evaluates cognitive development, emotional state, systematic influences, risk comprehension, and maturity level. Since the Family Law Reform Act 1969, anyone 16 years old and above are assumed competent. If there is controversy in this assessment, an impartial psychologist is contacted, and if there is further uncertainty, the matter goes to court. This process is so conducive to justice because it apportions a voice to all parties involved. Later came the Children Act 1989 which promotes additional consideration to the welfare of youth and highlights the responsibilities of the government and parental guardians in the treatment of minors. None of these laws help children much in the matter of refusing treatment, but they are certainly steps in the right direction.

The following are measures you can take to help address the problem of young people’s marginalized legal status in the medical world:

This is the simplest and most influential form of activism. Most adults have not questioned the current state of law and have heard nothing of its repercussions on the youth. Even worse, most young people are entirely unaware of their medical rights and lack thereof. Communicate with your town’s teachers and physicians, or even contact local journals to bring attention to the issue.

Write an informative message, or share this post, and spread awareness about the problems and solutions through your social media.

3. Contact Your Local Government

If a medical autonomy law is not in place for minors in your jurisdiction, propose the implementation of the mature minor doctrine or a standardized cognitive evaluation.