Protests are a good way to raise awareness and demonstrate support for an issue. They can also help people feel they are part of a bigger movement and inspire them to action. The goal of protesting isn’t just to yell and hold up signs, it’s to inspire change and influence your community. However, protests can be controversial, so you should think about the pros and cons in your particular situation.

Types of Protests

When people think of protesting, they often picture a large march, but there’s lots of different ways to get your point across.

- Sit-ins involve peacefully occupying a public space by sitting for a designated period of time and are popular in schools and colleges. Sit-ins for student rights have taken place outside the offices of college presidents and in high school courtyards. A sit-in demanding academic freedom could entail students sitting in on a class they’re not allowed to take, sitting outside a principal’s office, or occupying a school board meeting.

- Silent protests can be done as part of refusing to participate in a required activity. You can organize your protest on a specific day and include symbols of solidarity such as wearing a specific color. In 2010, 2,086 students at West High in Madison, Wisconsin gathered for a silent sit-in to protest a change in their curriculum.

- Walkouts are often used in schools and colleges where a group simply leaves at a designated time in an effort to express disapproval. They can often lead into a rally or march. They also can occur spontaneously, in response to some event. Walkouts have a long history in the fight for student rights, including Barbara Johns who organized a walkout to protest poor school facilities and segregated schools in the 1950s and Mexican-American students that protested unfair treatments and corporal punishment in the 60s.

- Protest rallies involve people making speeches about an issue. You can invite someone to act as an emcee to lead protest chants and songs and other community members who support your issue. Rallies are often used at the beginning or end of protest marches, but can be used by themselves. Rallies should be creative to bring attention to your cause. In 2014, dozens of students from the Providence Student Union in Providence, RI dressed up as zombies for a rally against standardized testing.

- Picketing and protest marches are similar except a picket stays in one place, like in front of a business, and marches go from one location to another. In most places, you will have to remain on the sidewalk or other public areas unless you’ve obtained a permit from your local government.

- Boycotts are refusals to buy a product or participate in an activity. Boycotts can happen alongside a protest and are good to use as a last resort- just the threat of a boycott may be enough to make your opposition back down.

Planning Your Protest

- Use your protest as part of a larger campaign. Depending on what your issue is, you should make sure that you’ve also used other methods to create change. If you are protesting a law or policy, let the people responsible know your complaint and give them a chance to respond. And since not everyone will be comfortable with protesting, make sure you are being inclusive by encouraging other ways for people to show their support, such as making phone calls, writing letters, or organizing a boycott. Holding a protest where not enough people show up might not help your campaign as much as other tactics, so you should make sure you have enough people to participate.

- Decide on a time and place. Protests can happen anywhere, but you should arrange your protest where it will be seen by as many people as possible. Some options include the sidewalk in front of a business, government offices, your school, or a park. If you’re protesting on private property without permission, the owner can ask you to leave and call the police to remove you if you don’t. You should also pick a time when you can get the most people to attend the protest (like a weekend), unless you want to specifically target someone (such as a legislator) and pick a time when they’ll be around. Obtain a permit, if needed.

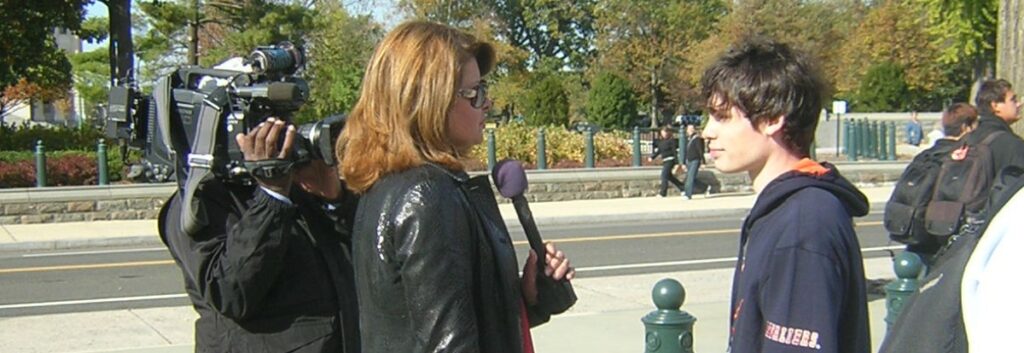

- Publicize your protest. Make brightly-colored flyers and posters about the protest and put them up around town and your school. Hand out pamphlets. Publicize in your school newspaper and on social media. Make a press release and send it to local newspapers, to websites and blogs, and to other organizations that may support your message. Call local newspapers and radio stations and ask them to promote the protest. Be prepared to talk about your issue in case you are asked for an interview. Even if people don’t come, they may be curious and research it.

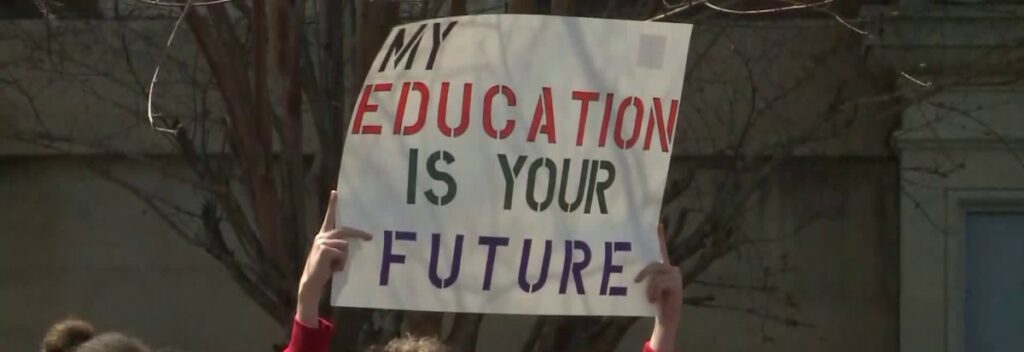

- Make a visual impact. Make brightly colored posters and banners with catchy slogans and bring some extra. Have pamphlets to help spread your message information on what you’re protesting to interested parties. Put the name of your chapter or group with your contact details so that people who are new to the issue will know who to contact to find out more. You can use chalk to write messages on public sidewalks.

- Be vocal. Learn or create some chants so that everyone knows what you’re protesting and why. Some examples include:

- What do we want? Voting Rights! When do we want them? Now!

- Hey, hey! Ho, ho! Curfew laws have got to go!

- Youth rights are human rights!

- Whose schools? Our schools!

- Document your event and have fun. Even if you are protesting something serious, you can make your protest entertaining. Take pictures and post them on social media. Live stream or record your protest. Keep the people energized and having fun.

Boycotts

Boycotts are similar to non-compliance strategies in that they are refusals engage participate in a certain activity. One common example which has been used by thousands of students nationwide is opting out of standardized testing. Students in Colorado have organized statewide campaigns and staged walkouts during the state-mandated tests. The Providence Student Union successfully petitioned the Rhode Island legislature to pass a three-year moratorium on using high-stakes testing as a graduation requirement through organizing rallies and conducting sit-ins at school board meetings.

Students, along with parents and teachers, have continued their boycotts against standardized tests even in the face of very clear consequences. States and school systems have threatened to fire teachers, fine parents, and suspend students for not taking standardized tests, and have begun doing so. But the the activists in the opt-out movement realize that the real power lies with the students – so the movement is not only holding together, it’s growing.

Youth rights activists have also organized boycotts and protests against convenience stores that have refused to allow more than one student in the store at a time as another successful example.

Making Art

Art has been a driving force in every major social movement. Songs, street performances, plays, films, literature, and paintings have the power to change people’s understanding of an issue, raise awareness, and bring activists together. Art provides a universal language that gives voice to individuals and communities and is accessible across social boundaries. Art that is made by young people or portrays young people in a positive way can also make youth feel empowered.

Types of protest art

- Performance stunts: Performance art is a great way to draw attention and raise students’ motivation to resist. Serbian student resistance movement Otpor! managed to topple their country’s dictator by combining satirical street performances with iconic branding, showing that the best way to create change may be to not take yourself too seriously. Students have also found creative ways to incorporate performance art into their everyday lives, bringing attention to important issues in ways teachers and other students can’t look away from. These include carrying trash bags to raise awareness of environmental degradation and carrying mattresses to raise awareness of sexual assault.

- Visual art: Filling your school with visual art, such as graffiti, is a great way to get a message to your whole community and show that you have the power. Visual displays in public places have brought issues out of obscurity and taboo and into public discussions, and visual art can be a part of public protests.

- Storytelling: Literature, film and theatre are great ways to tell stories with a message behind them or that simply empower other youth. Telling a story about the oppression youth face can show others what it’s really like more effectively than simply stating facts.

- Music: Music can move people, make people feel things and bring people together. Having musical performances or leading the crowd in song will add to any rally by building morale and getting everyone on the same page.

Going on Strike

Walkouts are an effective way to show that you disagree with your school’s policies. However, they traditionally last for a limited amount of time, and so they don’t force your school to comply with your demands. But if you organized enough students to boycott your school until they meet your demands, the administration would have no choice but to listen to what you are saying. And thanks to social media, you can band together with students across your county, your state or the entire country to organize an even larger boycott of school.

Strikes have been used successfully throughout US labor history. Workers use strikes to show their bosses that they will not go away or return to the job until their demands are met. You can keep a strike engaging by chanting, marching around campus and bringing whistles, drums or other noisemakers to draw attention to yourself.

It is worth noting that striking against your school could go against truancy laws. It is essential that you find out what the penalties for truancy are in your state. To avoid looking like stereotypical truants, it is important that all the students on strike gather near the school the school to protest every day. If you don’t think you’d be able to keep up outdoors protests, another option is to occupy the school itself.

In 2015, a handful of students in São Paulo, Brazil realized that their protests and their teachers’ strike weren’t enough to stop the state from shutting down 94 public schools. Perfecting a strategy that had been pioneered by students in Chile, they decided to boycott their classes, creating event pages on social media to mobilize their classmates to occupy their school and refuse to attend class until the government listened.

The group planned the action by role-playing the different scenarios they might face and agreed they’d need at least 40 students to close down the school. Once enough people showed up they changed the padlocks and locked the gates. Then they also reached out to other schools. A few days later, three schools were occupied- within two weeks, nearly 200 schools had been occupied. Teachers, families, adult activists and celebrities visited the schools to help the students and show solidarity, although it was always up to the students whether to let them in or not.

Despite the government devising a “war” strategy to discredit the students, the students spent the next month living in their schools. They organized their own classes, workshops, community meetings, sports events and musical performances, and began handling routine maintenance on the buildings they had taken over. They expanded their demands, using the occupation as a way to express their dissatisfaction with the school system in general as they created an ideal social and academic environment for themselves.

The students pulled this off by delegating specific tasks to everyone involved in the occupation, in the areas of food, safety, press, information, cleaning and external relations.

- The food committees cooked for the rest of the students with food donated by parents and neighbors; at many schools, students went door to door in the surrounding neighborhoods to explain the occupation to residents and ask for food donations.

- The safety committees deescalated any conflicts between students and closed access to the building, only letting in teachers, authorities, journalists, parents, and students who might pose a threat if permitted in the community meetings and making a list of everyone entering and leaving the building, which they destroyed at the end of the occupation to keep the striking students safe.

- The press committees publicized the occupation for other schools and the media; they drafted a statement explaining their reasons for striking which they hung up outside of the school and shared through email and social media, making sure that the statement adhered to what was decided at the community meetings without the interference of personal or partisan interests; as the strike continued they posted about daily life during the occupation to emphasize that they were doing meaningful work and not just messing around, and made several parody music videos where they changed lyrics of popular songs to messages about the occupation.

- The information committees made sure all of the striking students were kept up-to-date on the resolutions decided in community meetings, the times and locations of activities, and media reports on the occupation.

- The cleaning committees used cleaning supplies from their homes or that were left behind by the school’s staff, keeping it as fun as possible and encouraging turnover on the committee since it’s a task most students didn’t want to do; students who made hurtful comments would be immediately sent to the dishes roster.

Lastly, two delegates were elected in community meetings to attend meetings of neighboring schools while another two delegates were elected to speak with media and authorities; these delegates could be replaced at any time if they withhold information from the other students or make accept any proposals from the authorities without discussing them in community meeting first. When the government asked for these delegates to leave the occupation and negotiate with the governor in his office, the students insisted that the government send representatives to each school instead. And when the government tried to cut a separate deal with school, the students organized a regional conference with delegates from each striking school so the government would have to negotiate with students from all occupied schools at once.

Finally, the government conceded as the protests affected the governor’s popularity. The State Secretary of Education stepped down and many schools were still occupied for a month afterwards to make sure the government didn’t go back on their word and that no one involved with the strike would be punished.

With a strike as large and as focused as the São Paulo occupation, schools, colleges and law enforcement would not be able to hold anything against you- research has shown that when 3.5% of a population support a movement, it will always succeed. Holding back such a large group of students isn’t in anyone’s best interest. Neither is colleges refusing to accept nearly all their potential applicants, or throwing vast numbers of parents in jail because their children are skipping school.

Because of what would happen if a strike succeeds, this type of tactic can draw in students who wouldn’t normally be invested in activism. Since these tactics would need most of the student body on board in order to succeed, only use them for a broad solution that would radically improve the lives of everyday dissatisfied students, such as securing complete academic freedom. And don’t start acting until you’re sure you have most of the school on your side and you’re able to win.

It is worth noting that if a strike is not successful, it risks hurting your school’s community and your chapter’s reputation. Before going on strike, you should run through the different ways the strike could go, what you’re risking by striking, and how likely the strike is to succeed.

It is also important to be flexible. Your tactics will be influenced by accidents, other people’s reactions to them, and necessity, so you may need to improvise to achieve your goal. Use your analysis of the situation to make sure you are in control of your tactics, instead of your tactics controlling you.

Most importantly, remember that it’s okay to feel scared and stressed out when organizing a protest, especially one on a huge scale. Allow yourself to feel whatever you’re feeling and deal with your stress and anxiety as they arise. Your emotions are valid, so don’t hesitate to take care of yourself and the people around you.

Know your rights

Sometimes protests are unpredictable, but you should have a plan for how to deal with the police if they show up. Have proof of your permit, if you have one. Make sure you know your rights as a protester and are familiar with how to deal with police in case you get stopped by an officer.

Missing Classes

If your protest involves missing class, you may be punished for having an unexcused absence. However, that punishment should not be any worse than if you missed class for another reason.

Make sure you’ve checked your school’s policies on the punishments for unauthorized absences as well as their guidelines for suspensions. If you are being threatened with a punishment that is more extreme, it is possible that your school is reacting to the particular stance that you are taking, and that could be a violation of your freedom of speech. In many cases, students who walkout in large numbers can be spared punishment since the administration would not practically suspend everyone, but this really depends on your school and the issue. In these cases, schools may just choose to punish the organizers.

Disrupting Classes

Schools could also punish you for disrupting other students’ right to an education. Legally, disruption is difficult to determine, but it can include interrupting classes, threatening or harassing others, violent behavior, preventing school events for taking place, or causing emotional distress. Sometimes even the behavior of others, such as a flood of calls from angry parents to the school, can be considered a disruption. However, if you are just walking out, the “disruption” caused may not be substantial enough to warrant any punishment.

Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has ruled on multiple occasions that students’ First Amendment rights do not apply when students are found guilty of disruption. Those rulings usually focus on the fact that classes and class schedules are disrupted and the students who remain in school are distracted during walkouts. Furthermore, federal courts have determined that “the First Amendment does not require school officials to wait until disruption actually occurs before they may act” (Karp v. Becken, Ninth Circuit, 1971). In another federal court case, (Dodd v. Rambis, Southern District Court of Indiana, 1981), the court ruled that students’ distribution of leaflets urging fellow students to engage in another student walkout was substantially disruptive to school activities. In that case, a judge explained: “The First Amendment does not require school officials to forestall action until disruption of the educational system actually occurs. Indeed, this is the very essence of the forecast rule.”

While the administration can punish you for disruption, they cannot prevent you from having a walkout, say by issuing a school lockdown, for example, without a legitimate safety concern.